Image: Getty Images/Max Dannenbaum

Image: Getty Images/Max Dannenbaum As the US eyes a five-year rule for satellites in low-Earth orbit, NASA has announced it will fund three studies to understand the growing problem of space junk and what policies might mitigate it.

With the escalating number of satellites in low-Earth orbit (LEO), space junk is becoming a real threat to spacecraft, access to space and the International Space Station, as well as the economy being built in LEO by the likes of SpaceX, Amazon, and traditional defense-aerospace players, including Boeing, Northrup Grumman, Thales, Lockheed Martin and Airbus.

As NASA notes, space junk consists mostly of mission-related and fragmentation debris, non-functional spacecraft, and abandoned rocket stages -all made by humans. NASA says it takes the threat of orbital debris seriously.

"Orbital debris is one of the great challenges of our era," said Bhavya Lal, associate administrator for NASA headquarters' Office of Technology, Policy, and Strategy.

SEE:What is Artemis? Everything you need to know about NASA's new moon mission

The research NASA is funding aims to understand the dynamics of the orbital environment and explore policies to limit the creation of debris and mitigate the impact of existing debris.

"Maintaining our ability to use space is critical to our economy, our national security, and our nation's science and technology enterprise. These awards will fund research to help us understand the dynamics of the orbital environment and show how we can develop policies to limit debris creation and mitigate the impact of existing debris," said Lal.

Last week, the Federal Communications Commission's lead chair proposed new rules to cut the number of years LEO satellite operators have to dispose of their satellites after a mission is complete from 25 years to five years. The proposal is being put to a vote by FCC chairs.

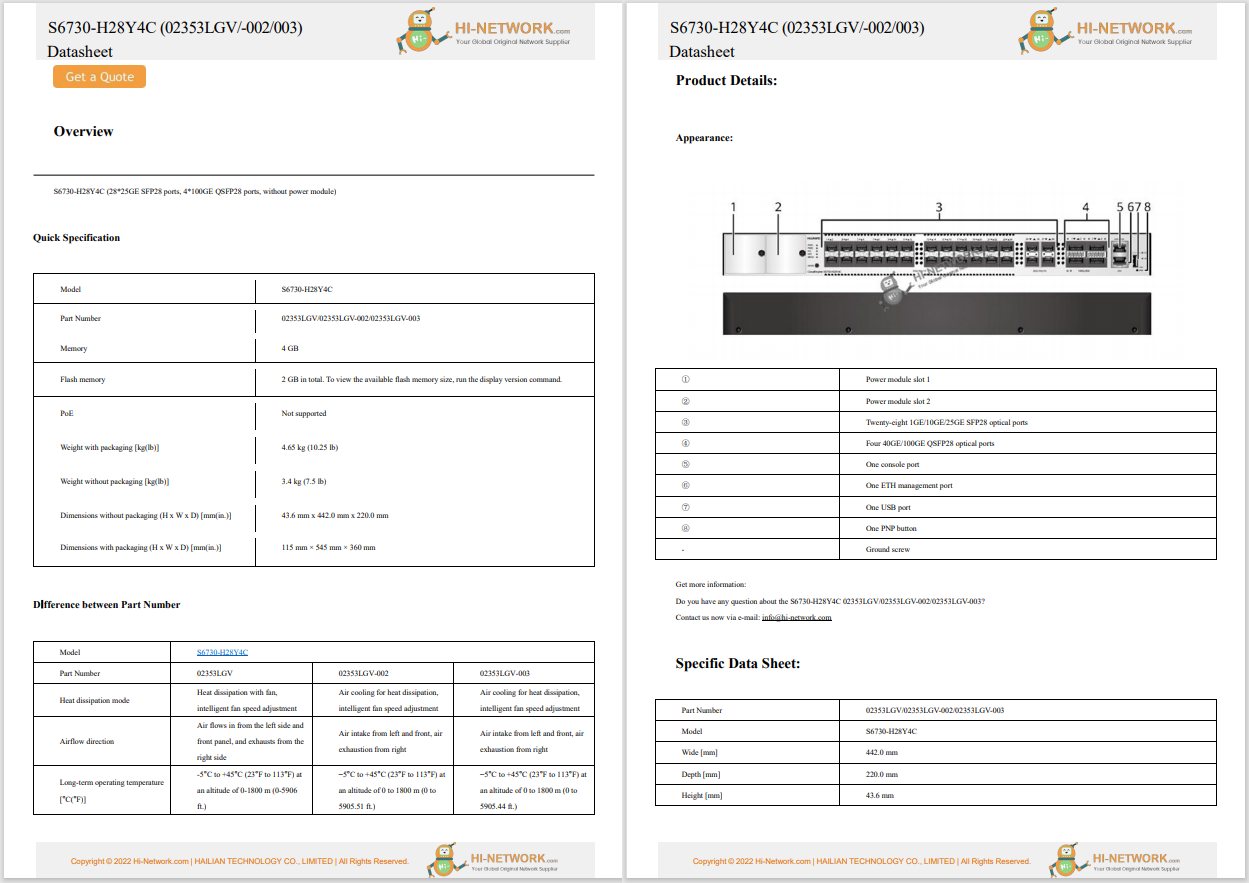

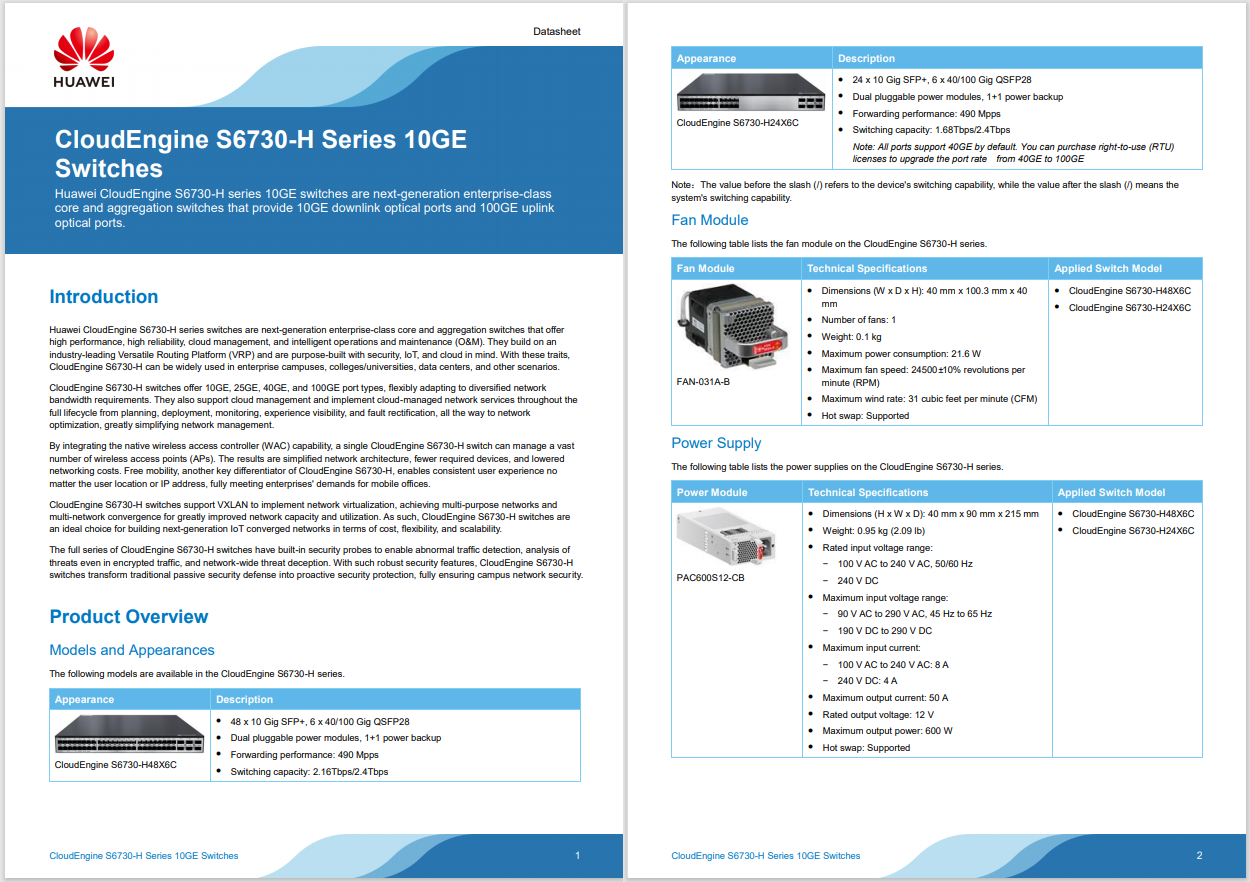

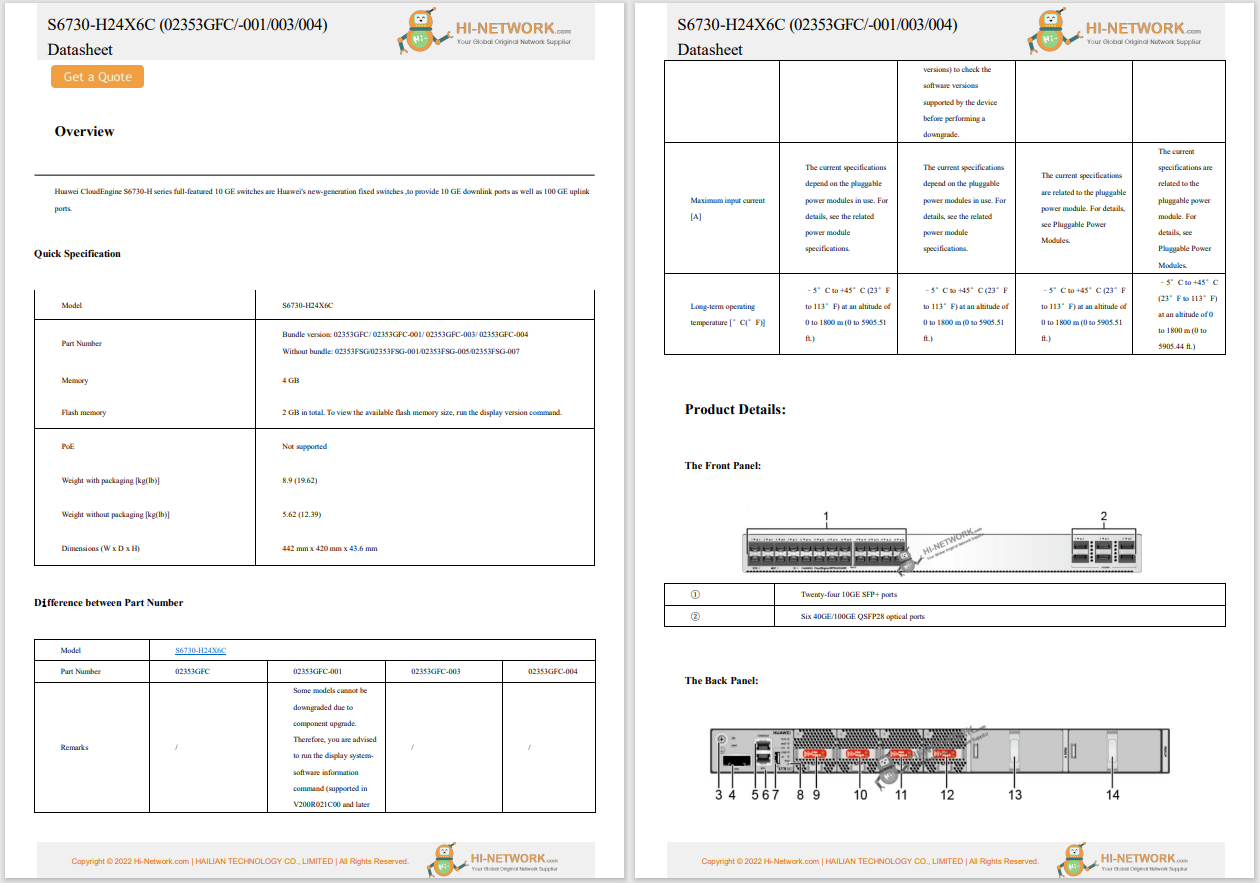

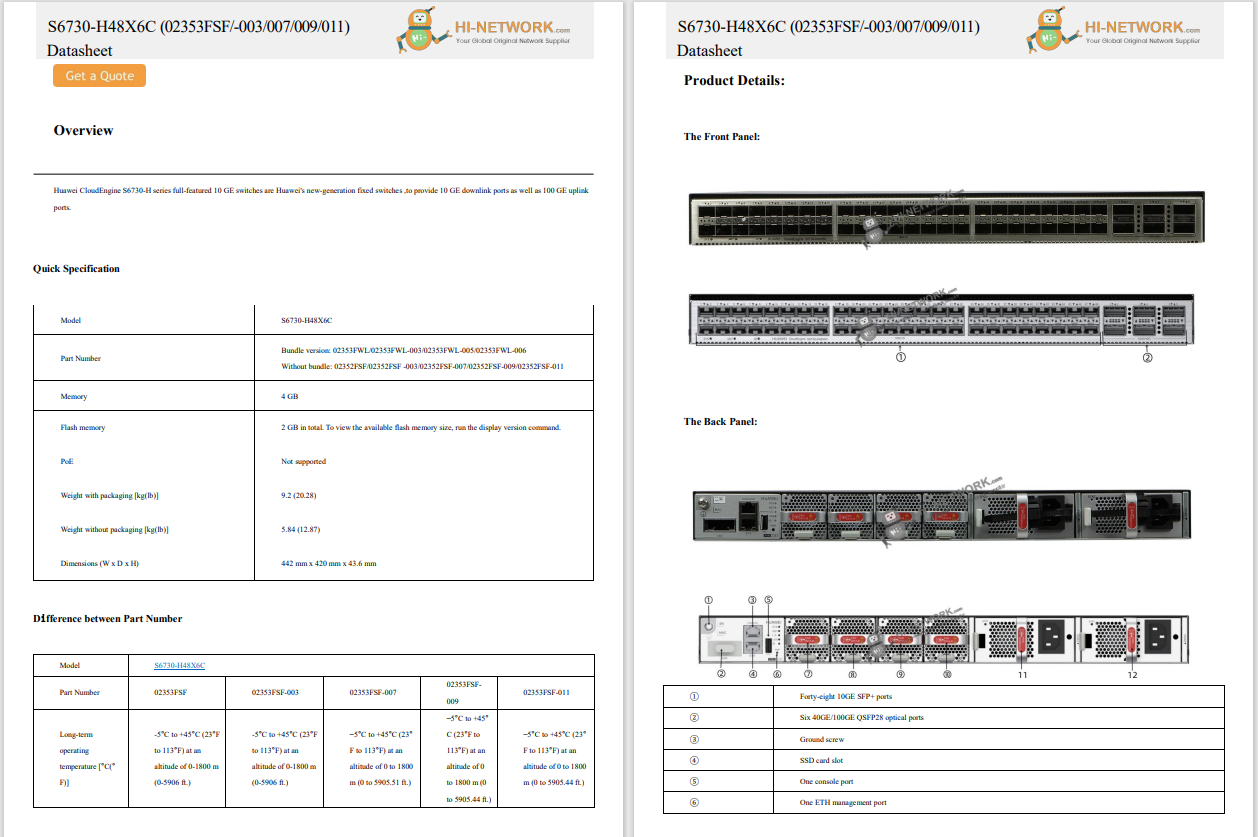

One research proposal to receive NASA funding is going to the creator of University of Texas' ASTRIAgraph, a crowdsourced space traffic-monitoring system (pictured below) that tracks active satellites (yellow dots), inactive satellites (blue dots), rocket bodies (purple dots), debris, and uncategorized matter (pink).

ASTRIAgraph shows a very crowded near-Earth orbit range, which is set to become more congested in future. SpaceX plans for its Starlink fleet of over 2,000 satellites today to expand to 42,000 satellites. In 2020, the FCC approved Jeff Bezos' Project Kuiper's plan to operate 3,236 satellites for its future SpaceX Starlink rival. China hopes to send up over 7,800 satellites, according to filings with the UN's International Telecommunication Union (ITU).

ITU manages radio frequency spectrum used by satellite operators, but there is no global regulator that controls how many satellites go up to space.

The Pentagon's Space Surveillance Network (SSN) sensors are tracking 27,000 pieces of space junk, both human-made and meteoroids, if they're two-inches (five centimeters) in diameter in low-Earth orbit and about one yard (one meter) in geosynchronous orbit.

SEE:SpaceX's Starlink internet is now heading to cruise ships in 'game-changing' deal

SSN doesn't track the far greater number of smaller bits of junk in near-Earth orbit, which are still large enough to threaten human spaceflight and robotic missions, according to NASA.

NASA says there are 23,000 pieces of debris larger than a softball orbiting the Earth at speeds up to 17,500 mph (28,163 km/h).

ASAT or anti-satellite tests are adding to the debris problem. China in 2007 controversially used a missile to destroy an old weather satellite for an ASAT test, creating over 3,500 pieces of large, trackable debris and many more pieces of untracked, small space debris.

In November 2021, Russia conducted a "direct ascent" ASAT test that generated at least 1,500 pieces of trackable orbital debris, according to US Space Command.

NASA says a panel of experts evaluated and selected the three proposals:

Yellow dots indicate active satellites. Blue dots indicate inactive satellites.

Source: University of Texas Tags quentes :

Inovação

Espaço

Tags quentes :

Inovação

Espaço