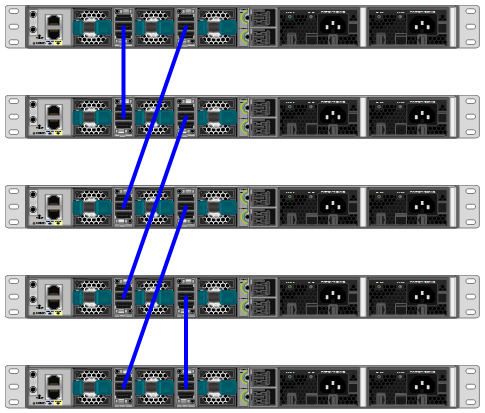

d3sign/Getty Images

d3sign/Getty Images When the consumer version of Google Glass appeared on the scene in 2014, it was heralded as the start of a new era of human-computer interfaces.

Learn about the leading tech trends the world will lean into over the next 12 months and how they will affect your life and your job.

Read nowPeople could go about their day with access to all the information they need, right in front of their eyes.

Eight years on, how many people do you see walking around wearing smart glasses?

The lesson here, as described by Stanford professor Elizabeth Gerber, is that "technology can only reach people if they want it."

Speaking at the recent Stanford Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence fall conference, she noted that "we didn't want to wear Google Glass because they invaded our privacy. We didn't want to because it changed human interaction. Just remember Google Glass when you're thinking about what can AI do -- people have to want it." (For a comprehensive overview of the entire conference, check out Shana Lynch's article at the HAI site.)

Designing "AI that people want is as important as making sure it works," Gerber continued. Another lesson learned was the adoption of AI-based tutors over Zoom during the COVID-instigated shutdowns of schools -- which served to turn children off from subjects. The same applies to workers who need to work with AI-driven systems, she added.

Also: Stack overflow temporarily bans answers from OpenAI's ChatGPT chatbot

Designing human-centered AI involves greater interaction with people across the enterprise and often is hard work to get everyone in agreement and on the same page as to which systems are helpful and of value to the business. "Having the right people in the room doesn't guarantee consensus and, in fact, results often come from disagreement and discomfort. We need to manage with and look toward productive discomfort," said Genevieve Bell, professor at Australian National University and a speaker at the HAI event. "How do you teach people to be good at being in a place where it feels uncomfortable?"

It may even mean that no AI is better than some AI, Gerber pointed out. "Remember that as you're designing, take this human-centered approach and design for people's work, sometimes you just need a script. Instead of taking an AI-first approach, take a human-centric approach. Design and iteratively test with people to augment their job satisfaction and engagement."

Perhaps counterintuitively, when designing AI, it may be best to avoid attempting to make AI more human-like, such as the use of natural language processing for conversational interfaces. In the process, the functionality of the system that helps make people more productive may be diluted or lost altogether. "Look what happens when someone who doesn't get it is designing the prompt system," said University of Maryland professor Ben Shneiderman. "Why is it a conversational thing? Why is it a natural language interface, when it's a great place for a design of a structured prompt that would have the different components, designed along the semantics of prompt formation?"

Also: AI's true goal may no longer be intelligence

The thinking that "that human-computer interaction should be based on human-human interaction is sub-optimal -- it's a poor design," Shneiderman continued. "Human-human interaction is not the best model. We have better ways to design, and changing from natural language interaction is an obvious one. There are lots of ways we should get past that model, and reframe to the idea of designing tools -- super tools, telebots, and active appliances."

"We do not know how to design AI systems to have a positive impact on humans," said James Landay, vice director of Stanford HAI and host of the conference. "There's a better way to design AI."

The following recommendations came out of the conference:

Also: Artificial intelligence: 5 innovative applications that could change everything

Tags quentes :

Negócio

Transformação Digital

Tags quentes :

Negócio

Transformação Digital