Image: Getty Images/iStockphoto

Image: Getty Images/iStockphoto GitHub has put the final touches on its Arctic Code Vault with a nearly 1.5 tonne steel box covered in AI-generated etchings that aim to entice future generations to explore it.

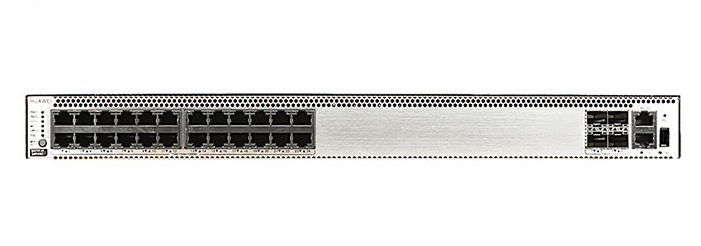

GitHub initially deposited its 21 terabyte 20 February 2020 snapshot of all public repositories shortly after the pandemic began, but none of its employees were there to witness or participate in it because of the pandemic. It left that job to local contractors.

The mostly QR-encoded snapshot is stored on over 180 reels of film that have, since July, sat 250 meters deep within a mountain in Svalbard, Norway, in a former coal mine. The spot is cold, close to the North Pole, and also near the world seed bank.

Also: How to run websites as apps with ease in Linux

GitHub never revealed what vault they were originally stored in, but whatever it was wasn't beautiful enough to signify their importance to future generations who will likely have little knowledge of the cultural and economic context the open-source code was generated in.

Given the archive's 1,000-year target, it's almost certain none of today's tech giants will exist then and nor will the tech they produced -from networks to software, smartphones and programming languages.

The shiny new vault's AI-generated etchings were created by artist Alex Maki-Jokela, within the Arctic World Archive.

"GitHub's Arctic Code Vault is now a literal vault, with our archival film reels resting safely within its 1400kg/3000lb edifice. Even if its inheritors many centuries from now don't know what it is, they'll certainly recognize it's something extraordinary," writes Jon Evans, founding director of the GitHub Archive Program.

Evans says Alexander Rose, a designer and executive director of its partners, the Long Now Foundation, told him: "If you don't make it beautiful, it's for sure doomed."

While some may wonder what the point of the vault is given the long horizon, Evans has a few ideas.

"A worrying amount of the world's knowledge is currently stored on ephemeral media," he notes, referring to hard drives and CD-ROMs. Someone in the future might also need software that is otherwise lost.

Also: How I revived three ancient computers with ChromeOS Flex

But also, future historians could see the widespread use of open source and its volunteer communities as well as Moore's Law as historically significant. It also offers a bottom up view of the tech world rather than just the view from the top.

"Our hope is that by storing and indexing millions of repositories we have captured a valuable cross-section of the world of modern software," writes Evans.

Another potentially useful addition is the what the project calls the Tech Tree -a selection of works that are mostly human-readable describing how the world uses software today.

The Tech Tree is divided into thirteen sections covering how computers work and how they're connected; algorithms and dat structures; compilers, assembler, and operating systems; programming languages; networking and connectivity; modern software development; modern software applications; hardware architectures and hardware development, electronic components like transistors and semiconductors; technologies before electricity; function, culture and history written over the last 150 years; and cultural context.

Tags quentes :

Tecnologia

Serviços & Software

Tags quentes :

Tecnologia

Serviços & Software