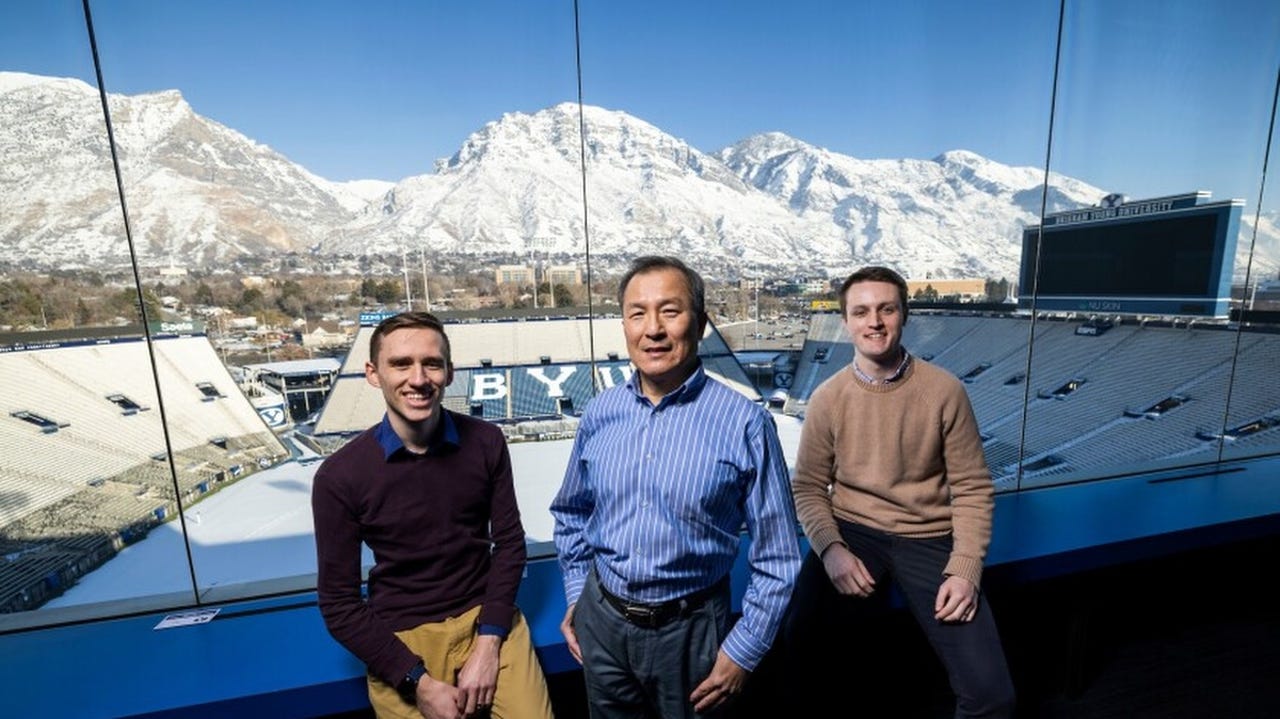

D.J. Lee and his team from the computer science department at Brigham Young University, standing in front of the college's football stadium in Provo, Utah.

Image: Nate Edwards/BYU PhotoA computer science department at Brigham Young University has changed forever how football game-tape analysis is planned and carried out.

This step change matters because it's the bedrock of game-winning strategies. The innovation comes from D.J. Lee, professor, and director of the Robotic Vision Laboratory in the Electrical and Computer Engineering Department at Brigham Young University (BYU), who -- along with researchers Jacob Newman, Andrew Sumsion, and Shad Torrie -- might have just provided football coaches with a dream assistant who can complete analysis like no one else.

Also: Why the next NFL star could be a data scientist

This ground-breaking solution uses machine learning, neural networks, and computer vision to save hundreds of hours of tedious work in tagging home and opposition players, tracking their movements and accurately identifying formations that can inform a counter-strategy.

Football, as you are probably aware, is a game where teams live and die by their strategies. This significance helps to explain why the NFL doesn't want the process of researching an opponent to resemble a Cold War spy thriller. Its "Game Operations Manual" states that "no video recording devices of any kind are permitted to be in use in the coaches' booth, on the field, or in the locker room during the game."

Also: This AI system will completely change your experience at sporting events

No devices? No problem. The information-gathering process is so critical to eking out a competitive advantage that furtive scouts sit in the stands with binoculars trained on coaches and their assistants, trying desperately to detect hand movements and gestures that could offer any insight into their plans. (Apparently, there's no credible evidence that this approach works, largely because, without video, it is so difficult to get right, especially with all the fake calls employed.)

This lack of success means analyzing game tapes is the only option available.

The stop-and-start nature of football, often involving a gradual, steady march down the field in various kinds of formations is fundamentally different from more fluid, free-flowing sports like soccer -- but the strategic nature of football also makes it perfect for analysis.

In football, coaches and their players get countless organized opportunities to execute different strategies on every down and formulate specific tactics for every play, whether you are on defense or offense.

If you have done your homework well, and the footage Gods have offered up some unique insights, you have a shot at using them to outwit the other side.

Veteran football player and NFL scout Mark Lillibridge, talks about how, through watching tapes repetitively, his team discovered how one particular and fearsome fullback on an opposing team had developed a tell -- or a habit -- of "ever so slightly cran(ing) his neck to get a view of the player he was about to block."

Also: This AI chatbot can sum up any PDF and answer questions you have about it

These sort of epiphanies score points, win games and burnish careers. "There's nothing better than being 90% sure what play was about to be run," says Lillibridge.

This kind of insight explains why, even today, players start their preparations for the next game by watching footage of the one that just concluded, either together or in their separate units so they can prepare for strategies like pass rushes and blitzes. Many teams allow their players to download footage onto their iPads from almost anywhere.

But footage by itself does not make a player victorious. The real, grueling work takes place in the departments built to generate game tapes.

There, team personnel have to correctly identify players from opposing teams, their locations, positions and movements, as well as offensive and defensive formations.

They then need to make insightful observations on everything from overall strategies being employed by the opposition coach down to granular details about player movements and tendencies, so that countermeasures can be hatched.

Also: This machine learning project could help jumpstart self-driving cars again

That level of analysis involves a lot of hours. There are 55 players on each team's roster and 32 teams in the league. If you're also scouring tapes historically -- looking at plays from previous years to add more depth to your analysis -- then that's enough time to ensure you never see daylight.

What's more, it's hard to get the analysis right. Game-tape prepping is painstaking work, especially for humans. For machine learning, on the other hand, it's a piece of cake.

When the BYU engineering team started to look at their college's football tapes, it was quickly apparent that there was a big problem: there were no consistent workable camera angles.

At the college level, camera placement for games tends to be all over the place and not all players on the field are always visible by one camera angle. Then, there is the quarterback, who stands in front of the center blocking him. And the defensive players closest to the line of scrimmage are also obstructed by the offensive line.

Also: This new technology could blow away GPT-4 and everything like it

For a machine-learning algorithm to work effortlessly and automatically, it would have to be able to rely on angles that are consistently the same across all college game footage involving BYU or any of their opponents.

So, to save time, the team at BYU decided to come up with a proof of concept, using a game-based solution instead of waiting for the camera angles to sort themselves out.

"We then stumbled upon a solution -- the Madden 2020 NFL video game," Lee told ZDNet. "It actually allows you to position the camera view in a variety of different places and gave us the control and consistency our algorithm needed."

The camera view that proved most useful was an overhead, bird's-eye-view, vantage point where almost all the players could be seen. Coupled with end-zone views that showed both the offense and defense, every player could be covered consistently.

Also: The best sports streaming services

The solution worked and the BYU team's algorithm was able to identify and label 1,000 images and videos from the game.

"We obtain greater than 90% accuracy on both player detection and labeling, and 84.8% accuracy on formation identification," the researchers reported.

In fact, the formation identification accuracy hit 99.5% if the more complex I formation -- which had several player views obstructed -- was dropped from the algorithm.

So, what does all this success mean for the immediate future of football analysis? "Well, you could get access to the broadcast video of NFL games, filter out commercials, graphs that they put on the screen, but it's not as efficient. It's a lot more work," said Lee.

"You don't really need to be have a bird's eye view, right? You just need to be up high, so we can see the whole field. And if you cannot see from the overhead camera, you should be able to see from the end zone. Once you get that all synchronized, you're in business," added Lee.

Also: Generative AI is changing your technology career path. What to know

Well, guess what? The NFL has long-published every NFL game in the season using the All-22 format -- a camera perched high up at the 50-yard line, where you can see every player on the field.

Even eager fans can access this data for$75 a year.

NCAA college football conferences started doing the same thing last year, but the initiative is still in its infancy.

In other words, what BYU's algorithm has allowed with Madden 2020 can easily be transposed onto the NFL as we speak -- and it should only be a matter of time for college teams to follow suit.

Also: The best fantasy football apps

I asked Lee what would happen when algorithms, with total command of every strategy, counter-strategy, and player strength and weakness, become more effective coaches than humans, instructing players directly via helmet mics.

"That's scary," said Lee. "Coaches become obsolete. That's probably not that cool."

Tags quentes :

Negócio

Grande volume de dados

Tags quentes :

Negócio

Grande volume de dados